“Science guards the quality of knowledge”

An interview with Gerard Steen

“I started out with English language and literature at the VU, after which I spent a year at the University of Birmingham to study with the novelist and literary scholar David Lodge. When I came back I realized I wanted to do General Poetics, which was available at the VU as well. So I did two Masters: English Language and Literature and General Poetics. After I got my MA in English, I considered becoming a writer. But then I traveled in South America for a while, and I missed academia. That is why I finished the MA General Poetics, and decided to go into academic life. I got a PhD project with Elrud Ibsch, on metaphor and literary reception. My thesis wanted to examine whether literary metaphors were treated differently if you thought you were reading a literary text as opposed to when you thought it was a journalistic text. I did experiments where I gave the same text to one group of people and told them it was literary, and to another group who thought it was journalistic. It turned out that readers paid a lot more – and different, attention to the metaphors in the text when they thought it was literary. I got my doctorate degree in 1992, and then I got two half time jobs both at the VU in General Poetics, and in Tilburg at Discourse studies. I worked in Tilburg until 2000, and then I came back to the VU, and became a lecturer in the English Language and Linguistics department. I got a VICI grant in 2005, so from 2005 until 2010 I only did research, and supervised 6 PhD students. I was appointed full professor then, on a personal chair in Language Use and Cognition, in 2007. In 2013, I then got appointed to the CIW (‘communication and information science’) chair. I was appointed to the same chair at the UvA here on the 1st of January last year.”

“I decided to change to the UvA, because I had been at the VU for 39 years on end: I came in as a student in 1975, and in 2014 was asked to apply here. Actually, lots of things were changing at the VU and I was working very hard to make those changes successful, so I did not really want to go. But during the interview meetings here at the UvA we got so interested in each other that I thought that this would be a nice opportunity to do something else for the last ten years of my career. There are lots of differences between the UvA and the VU, but they are mostly kind of subtle. The biggest difference is that this faculty is much bigger than the Humanities Faculty at the VU, which means that there are more disciplines, more colleagues; it is easier to find somebody with a certain expertise. At the VU, there were seven full professors; the UvA has about twenty just within in Linguistics – including the modern languages. So you can choose your friends, or colleagues, from a bigger pool of possibilities.”

“At the VU, professor Elrud Ibsch introduced reception theory into Dutch poetics. This had to do with moving research away from the meaning of texts to how readers realize this meaning; not only historically and theoretically, but also empirically. The idea of reception theory is that meaning is not just in the text; it is in the interaction between the text and the reader. Language and discourse are instructions for the reader to construct meaning, but you have to bring world knowledge to the text to complete the representations. So there is a lot of variation, between how people in different times, spaces, and groups understand language and texts. This is simply because language underdetermines meaning, and you bring a lot to the table that influences what your mental representations eventually look like. I think that the most important part of meaning is in our heads, but the prompt is in the language, and the way it gets finished and used is in the interaction between people. But there is no meaning without anyone representing it mentally; which is why I am most interested in the psychology of language use.”

“I knew that I wanted to be a researcher from the moment that I met professor Elrud Ibsch. She was so inspiring because she was intellectually very high standing but she also had a great social and cultural enthusiasm as to what science can do in society. She really felt that science could make a contribution to society, in the sense that it guards the quality of knowledge. Our policies, for instance in terms of education, should be based on knowledge, and this eventually comes from science. So, even though not all scientific knowledge has direct use for society, the construction of science has lots of possibilities for application. For me, this was my excuse to be a scientist for the rest of my life: it means that I do not have to do outside work and heavy lifting; I like going to the gym but at work I can just use my mind.”

“An example of the practical applicability of my work on metaphors is for instance how patients talk about their illness. We see for example that cancer patients often express the way they experience their cancer in metaphorical terms. On the one hand, it can be highly useful to talk about your emotions in metaphorical terms, because that is the only way we can talk about our emotions, but it can also be hampering. If you see cancer as a fight or as a war, and you have been diagnosed as a terminal patient, then you have lost the war. How does that empower you to actually go through those last stages where you cannot get rid of the cancer anymore? Maybe you need another metaphor to keep you going, and to increase the quality of your life.”

“Lakoff and Johnson’s famous theory is that because there is so much metaphor in language use, people also think metaphorically. Part of our VICI project was to annotate an excerpt from the British National Corpus and estimate how many words were metaphorical. Because of that method, we can now say that probably one in eight words is metaphorically used. That means that in every utterance there is at least one metaphorically used word, because utterances are on average eight words long. However, I do not believe that Lakoff and Johnson are right: not all of those words activate the source domain that they are supposed to tap, which presupposes that we even know what those source domains are, which is a tricky question. I think that a lot of words are processed by means of lexical disambiguation, i.e. the words have conventionalized metaphorical meanings, which means that the meaning are already available in your mental dictionary. If you take for instance all temporal prepositions, like ‘before Christmas’, ‘after Christmas’, ‘in a week’, etcetera. It would be crazy to assume that we would go to the spatial domain first, and then construct the temporal sense. So when you hear a particular word, for instance ‘in a week’, both the non-metaphorical and the metaphorical senses get activated at the same time, the irrelevant – literal – meaning is suppressed, and the metaphorical one is used. That means that people do not go to the source domain anymore to construct the target domain meaning, but that it is already there and they just use it. Thus, most metaphor may not be processed metaphorically, at least not according to the model of Lakoff and Johnson. At the same time, this only holds for most metaphors. It is clear that there is specific cases of metaphor where people do go to the source domain and then construct a target domain meaning, for instance for all novel metaphor. Then, there is no metaphorical sense already available, which means that you have to construct it online. Or any extended metaphor, where you talk about one thing in terms of something else for a number of utterances in a row: where you set up an explicit analogy between two things. That is deliberate metaphor use: using metaphor as a metaphor between people. The users do not have to consciously realize it, but at least they pay attention to the source domain as a separate referential domain in itself. The main prediction of my Deliberate Metaphor Theory is that if the metaphor is used deliberately, the source domain will be activated in the reader’s mind, and only then will the source domain have a potential to affect the representation of the text. If the metaphor is not deliberate, then we as linguists can point to the source domain, but it will not have any effect on the representation, because it is not used as such.”

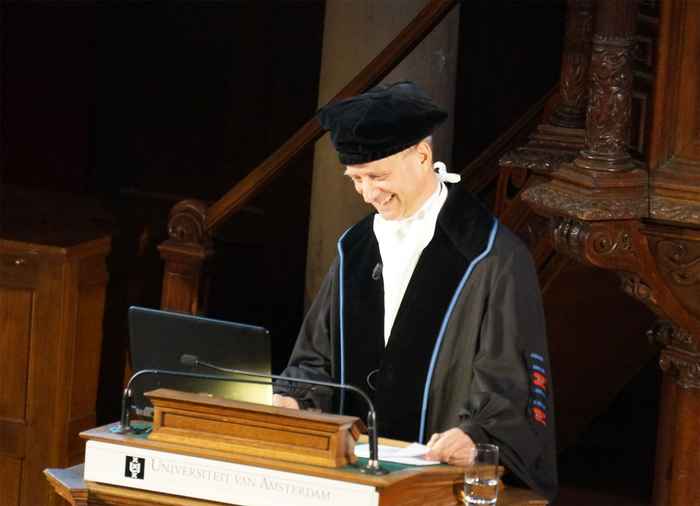

“My inaugural lecture at the UvA was about the relation between language and discourse. I think that when we talk about language, we mainly talk about utterances. That is, we are talking about little bits of language that are based in grammatical units that eventually boil down to the clause – or the act, as Functional Discourse Grammarians would say. Discourse on the other hand is all about text in code in context. It is made up of these little bits that we call language, but the level of structural-functional aggregation is a level higher. Therefore, I argued that we cannot describe the one in terms of the other. We need two different theoretical frameworks: one for language and one for discourse. There is no discourse without language, and there is hardly any language without discourse, but they have different levels of abstraction. I do not think you can reduce any biological organism to the chemistry either; there levels are also important. The main point is that you have two levels of information structures and that they each follow their own patterns of structures and functions, and that they need to be described at those levels in such a way that you can make connections between the two phenomena, but you cannot reduce the one to the other or the other way around.”

“For the five past months, we had a visiting researcher here from Italy: Valentina Cuccio. She is a philosopher of mind and language, who worked with people like Vittorio Gallese, the discoverer of mirror neurons. Valentina came here to write with me about the neuroscientific foundations of DMT. During the five months that she was here we put together a book, which has been accepted for publication. We are sketching how everything I say about mental representations can actually be grounded in the brain. We are reinterpreting the existing evidence about the brain, such that we can use it to support our argument about DMT. This is all preparatory work for neuroscientific experiments that can follow up on that. I am really exited about this.”

“Our lab is organizing the Metaphor festival, which will take place on 1 and 2 September. It is a low threshold, informal conference about metaphor research, but also about anything else in rhetoric. It is a yearly conference that is in Amsterdam for the first time this year; it ran in Stockholm for the past ten years. But the founding organizer of the conference died a year and a half ago of breast cancer. They organized it one last time last year, but they felt it was not the same, and the other people who ran it were both on the point of retirement. So then they asked if we could take over. We would like to on the one hand continue the tradition, and on the other hand maybe explore the notion of a festival a bit more emphatically. So the conference will have two days of academic papers, and the third day, on 3 September, will be a day where we will invite the academics to be a little bit more playful: we are going to do metaphor slams for example. Also, we are going to try to bring in the non-academic world, because we would like to challenge the academics to think more constructively about what their work can do for people in for instance the creative industry, organizational management, and health communication.”

“I do not like the label cognitive scientist. I think the label Cognitive Science is too general, too vague; Cognitive Science is not even a coherent domain. The label has been kind of hijacked by people in the Humanities to suggest that they are scientists, which in some cases they are not. It is the job of scientists to produce reliable ad valid knowledge, on the basis of a tradition that you make use of and that you add something to, in a way that your knowledge is testable and criticisable. I think that a lot of people in the humanities who label themselves as cognitive scientists do this mostly on the level of theory formation. However, not a lot of those ideas are actually rigorously tested. In my opinion you should be prepared to work towards experimental research, most certainly for those topics where this is possible. It is of course very hard to do this with historical work: you cannot experiment with people who are dead. But even historical work needs to be informed of the state of the art in for instance reading research. If you make claims about how language and discourse work, then you should be able to guide it towards testable research. To me, that is science: if you are not prepared to do that, you are not a scientist.”